Click Images Below to Expand Them

Select/click the images above to expand them then click/tap to advance to the next picture. Also, Turn your cellphone side ways for horizontal pictures, and straight up and down for vertical pictures.

The first 4 pictures above depict Hollowstem Joe Pyeweed (Eutrochium fistulosum) which grows 6 to 10 feet tall depending on sunlight exposure, soil fertility, and soil moisture. It's native to wetlands and other environment with seasonally wet or permanently wet soil conditions. This Joe Pyeweed is also adapted to moderate moisture conditions helping it to adapt to garden conditions. Essentially all of the organic matter that large herbaceous plants like Joe Pyeweed create above ground gets broken down and consumed by soil bacteria, fungi and small insects. So the more biomass (organic matter) a native plant creates - the more biomass is converted into energy for living organisms whom's energy works its way up the food chain. This plant's flowers are also one of the most popular for supporting native pollinators. If you want to grow Joe Pyeweed species in somewhat drier soils, just apply 2-3 inches of extra water per month throughout the summer months.

The last two pictures in the above gallery are of “Joe Pyeweed” - Eutrochium maculatum. This is a more northern Joe Pyeweed which is also much shorter than the aforementioned Hollowstem Joe Pyeweed Eutrochium fistulosum. The bloom shape is also flatter in comparison. If you’re within its native range, this Joe Pyeweed is friendlier to garden settings due to its average height of 4 to 6 feet tall.

Germination Tips: For all species of Joe Pyeweed, Cold Moist Stratify for at least 45 days before sowing on the surface in early to mid spring. Compress the seed into the medium. They will germinate within 10 days if the surface is kept moist.

Click Images Below to Expand Them

Select/click the images above to expand them then click/tap to advance to the next picture. Also, Turn your cellphone side ways for horizontal pictures, and straight up and down for vertical pictures.

Tall Coreopsis (Coreopsis tripteris) is a prairie and savanna plant adapted to seasonally wet soils as well as drier soils under intense root competition from other plants. The small flowers are most favored by small native solitary bees and small butterflies. This is one of the longest lived plants of the Coreopsis genus. It's deep root system and robust growth allow it compete long-term with other aggressive plants native to the ecosystem known as the Tallgrass prairie such as Big Bluestem and Indian Grass. It ranges 5 to 9 feet in height depending on available resources. Planted in dense vegetation within gardens, it may have enough root competition to stand up straight. It’s best to never water this plant within gardens or else risk it flopping . As a background plant in pollinator gardens it adds a wispy fine textured tall layer that catches each breeze that passes animating the garden. If planted on a wood edge or the side of a house where it receives shade, it will lean away from the wood edge or building structure making it more prone to flopping. So it’s best within gardens to have it planted in full-sun away from shading objects such as trees and buildings.

Germination Tips: Moist Cold Stratify for 45-55 days before sowing on the surface in early to mid spring. Compress the seed into the medium. They will germinate within 10 days if the surface is kept moist.

Click Images Below to Expand Them

Select/click the images above to expand them then click/tap to advance to the next picture. Also, Turn your cellphone side ways for horizontal pictures, and straight up and down for vertical pictures.

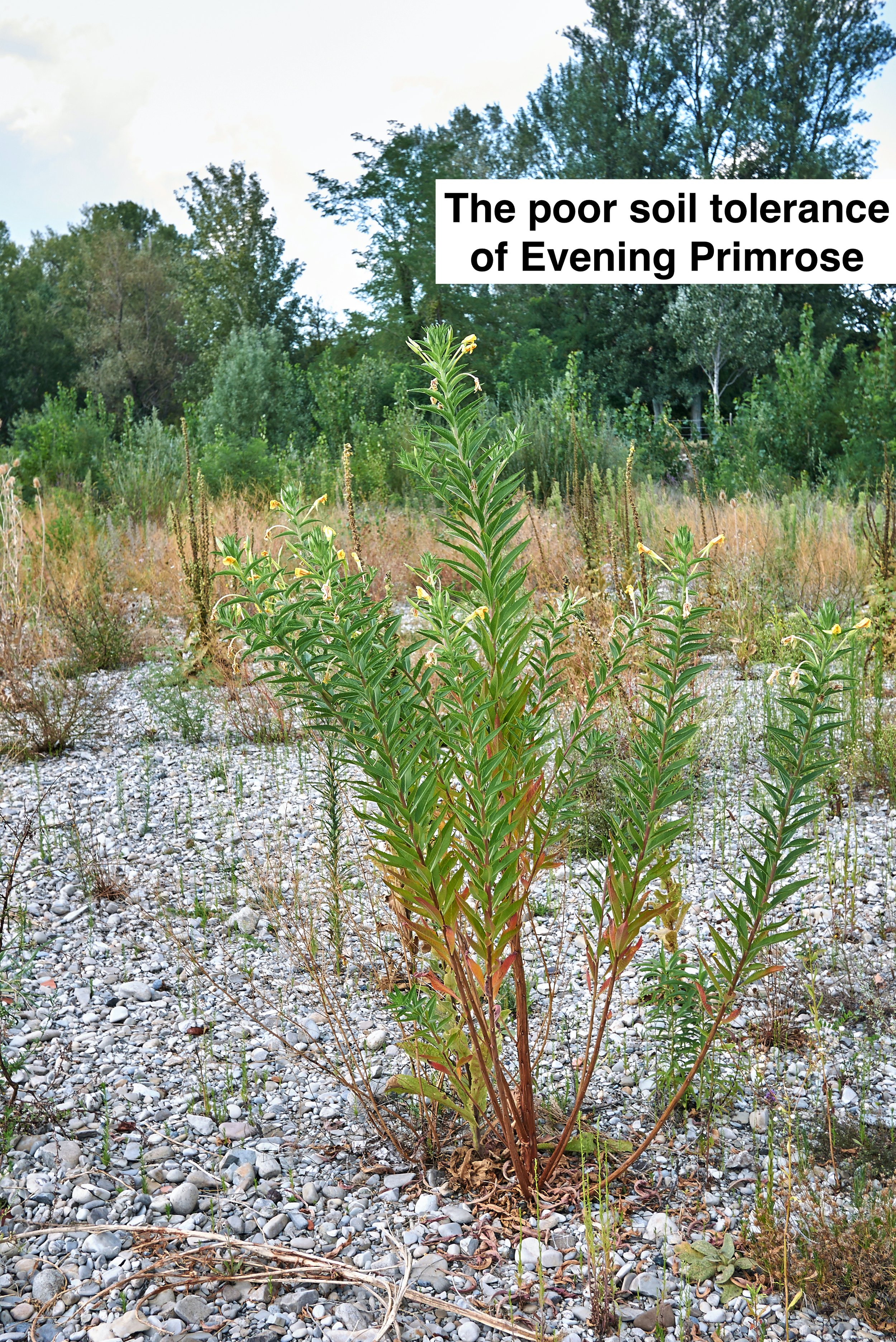

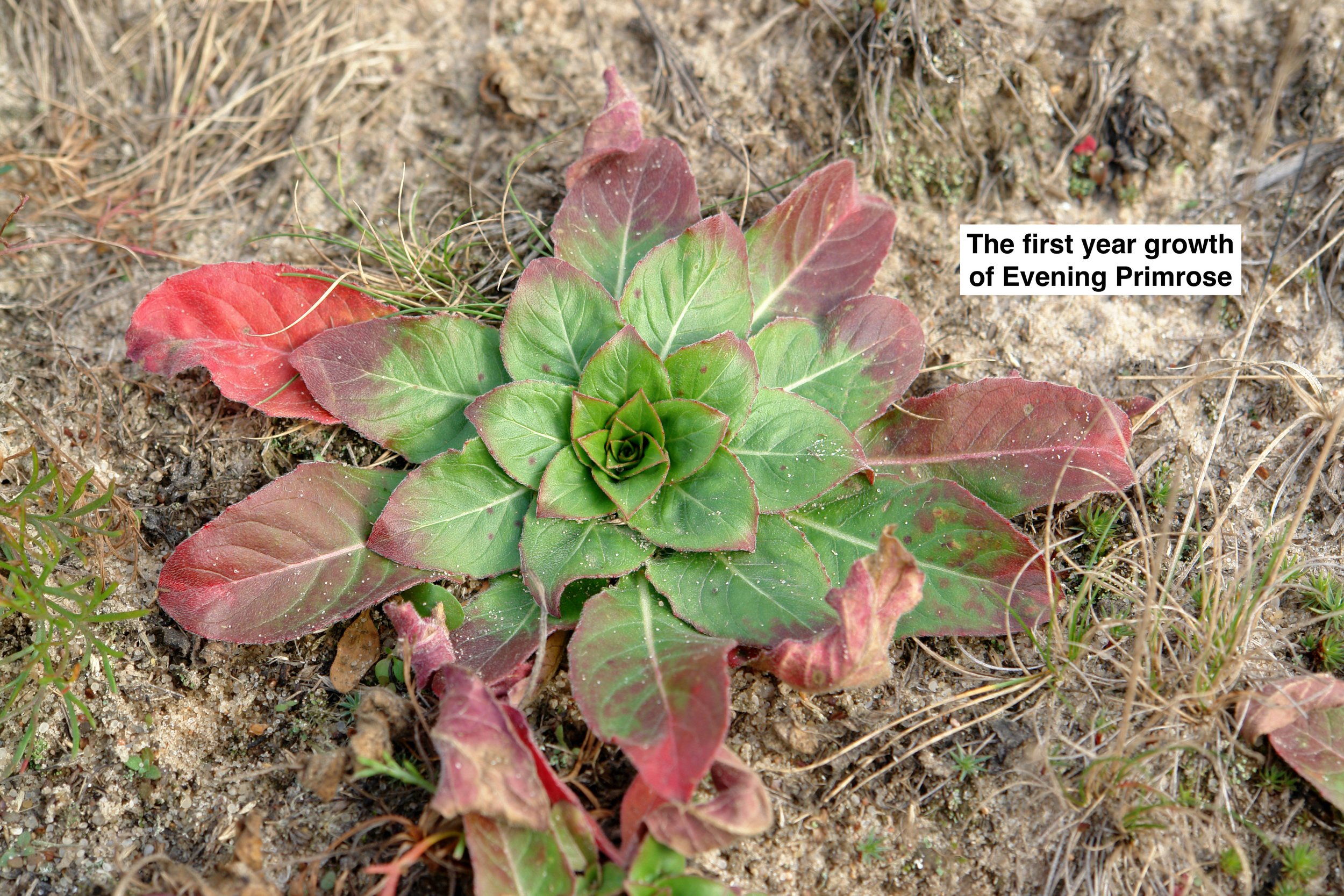

Pasture Thistle (Cirsium discolor) is a native biennial wildflower that explodes with growth during it's second year of life. The stems will commonly grow to heights over 7 feet tall, attracting caterpillars, aphids, and other plant consuming insects to take advantage of its large biomass. The flowers are of some of the most popular with native bumble bees, solitary bees, and butterflies. When it comes to bumblebees, there aren't too many plants to bloom in the late summer that are as popular as native Thistle plants. The seeds a highly favored by Goldfinches. Pasture thistle is adapted to moderate moisture as well as fairly dry soil conditions. The first year root is an edible, native plant agricultural crop. Harvest it like Evening Primrose through seeding it in the spring within a bed of itself, fostering the basal rosettes throughout the year, before digging it up in the fall or winter.

Germination Tips for plugs: Cold Moist Stratify for 40-50 days before sowing 1/4th inch below the surface and compressing the medium in the spring time. Keep surface moist during germination period. Plant the resulting plug in early summer with plenty of water during the establishment period.

Receive 40% off of our Native Plant Propagation Guide/Nursery Model book when purchased as a package. deal with either our Native Meadowscaping book or our Native Plant Agriculture book at this link.

Learn about what our Native Meadowscaping book has to offer here at this link.

Learn about what our Native Plant Agriculture Vol. 1 book has to offer here at this link.

Learn about what our Native Plant Propagation Guide & Nursery Model has to offer here at this link.