If viewing on a Cell Phone, turn the phone sideways for better orientation of article and pictures. If the article isn’t displaying well, it will display properly on a laptop, tablet, or desktop computer.

Picture: Young American Hazelnut shrubs in spring with their leaves protected from deer grazing.

In the United States; wherever Wolves and Mountain Lions have become rare or absent, deer populations are at unnaturally high population densities. Whether planting on large scale rural land, park land, or in your front/back yard, there’s a high likelihood deer will evaluate your native plants, mostly through their noses, to determine their palatability. This part 1. post focuses on helping you establish native trees and shrubs effectively through protecting them from deer. Our Part 2. post will provide things you can do to increase the growth rate/establishment rate of native trees and shrubs.

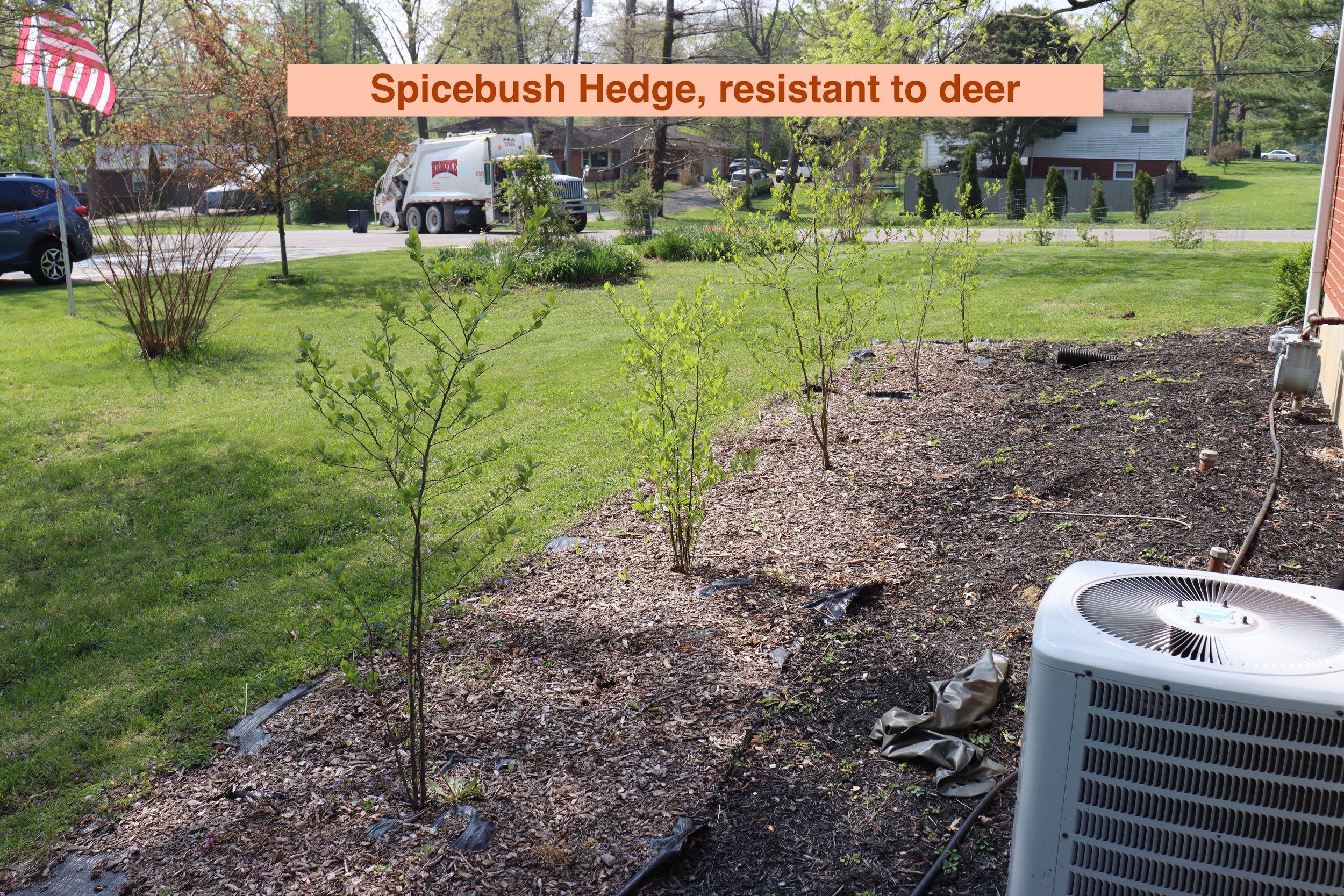

Plants like Speciebush, Ninebark, Pawpaw, Black Aronia (Aronia melanocarpa) have high deer grazing tolerance (pictured below) which means there are chemicals in the leaves of the plant that make them unpalatable to deer. Other plants like American Hazelnut, Native Crabapples, and Winterberry Holly have lower deer grazing tolerance. They may have been moderately tolerant when deer populations were regulated by a wide abundance of natural predators. But in this modern day condition of unnaturally high deer population densities; some native plants can get completely defoliated by deer grazing, preventing them from growing or establishing.

For the Pictures Above: Select/click the images above to expand them then click/tap to advance to the next picture. Also, Turn your cellphone side ways for horizontal pictures.

Here’s a solution to your Deer issues. For all native trees and shrubs, put a welded wire fence around them. Even though some native trees and shrubs don’t require them for deer grazing protection; the welded wire fences also protect against Buck rubbing which greatly damages the bark and living tissue (Cambium) of native trees and shrubs. Bucks rub young native trees and shrubs to sharpen their antlers, rubbing off the velvet layer to prepare for mating season combat with other bucks.

Large hardware stores like Menards, Home Depot, and Lowes sell rolls of 50 feet to 100 feet lengths of 4 feet tall welded wire fencing. Deer graze up to a height of around 4 feet, so these fences protect the native trees and shrubs from grazing fully within the first 4 feet. At that point the Native Tree or Shrub should out grow the deer grazing line and grow upward above the fence. A couple of years of growth over the deer grazing line of 4 feet, you may want to remove the fence and reuse on other new plantings. You can usually do this safely, but the trunks may still need fencing protection from Buck Rubbing. If you can tolerate the fence aesthetic, it’s best just to leave the cages on for a full 5 to 8 years allowing the native tree/shrub to get big enough to withstand deer grazing and buck rubbing. If you really don’t like the silver fencing aesthetic, the big box stores also offer the same fencing in Black or Green. Though the color coated welded wire fencing costs more, it will become more invisible in the landscape aesthetically.

For the Pictures Above: Select/click the images above to expand them then click/tap to advance to the next picture. Also, Turn your cellphone side ways for horizontal pictures.

About 9.5 feet length of the 50 feet or 100 feet roll of welded wire fencing, will yield roughly a 3 feet wide diameter, circled fence. So a 50 foot roll will yield 5 fences and an 100 foot roll will yield between 10 to 11 3 foot diameter circled fences. Per foot, the 100 feet rolls are always cheaper than the 50 feet rolls.

Keep in mind, you can reuse these fences for the next 25 years. A 4 feet diameter is best for wide spreading shrubs like American Hazelnut, but plants that shoot upward like a tree, just need a 2 foot diameter circled fence with a length of 6.5 foot length of welded wire fence to be well protected. The 4 Prunus virginiana (Thicket Cherry) pictured above have closer to a 2 foot diameter, 6.5 foot length of welded wire fencing because they shoot upwards into a small tree. Thread a 2 or 1.5 foot long piece of rebar through the bottom rungs of the welded wire fence before hammering it halfway into the ground to support the fence. All of these materials are reusable long-term, and available at the big box stores such as Menards, Home Depot, and Lowes.

How to Close the Welded Wire Fence

To close the welded wire fence, watch the video above. You must learn how to close the welded wire fence before cutting them pieces from the 50 or 100 feet rolls. Alternatively you could close the fence with uv resistant zipties.

Watch the Video below to see how to establish Native Trees/Shrubs - The Mat (in the video) used around the Plant is important!

This article is only available here at Indigescapes.com, not Facebook. To make sure you don’t miss our website articles like this one, sign up for our email list at the bottom of this webpage.