Slender Mountain in a Native Meadow Planting

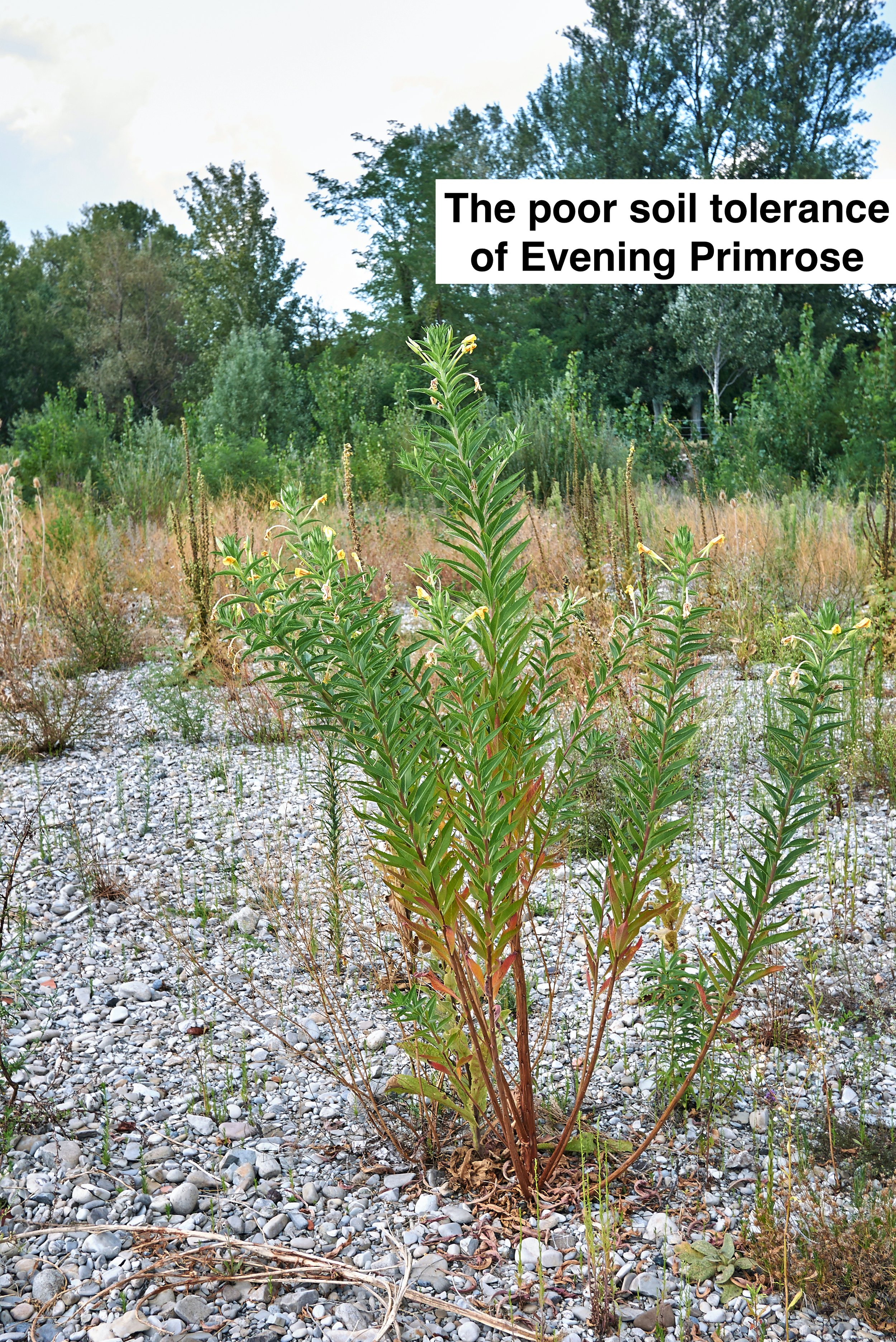

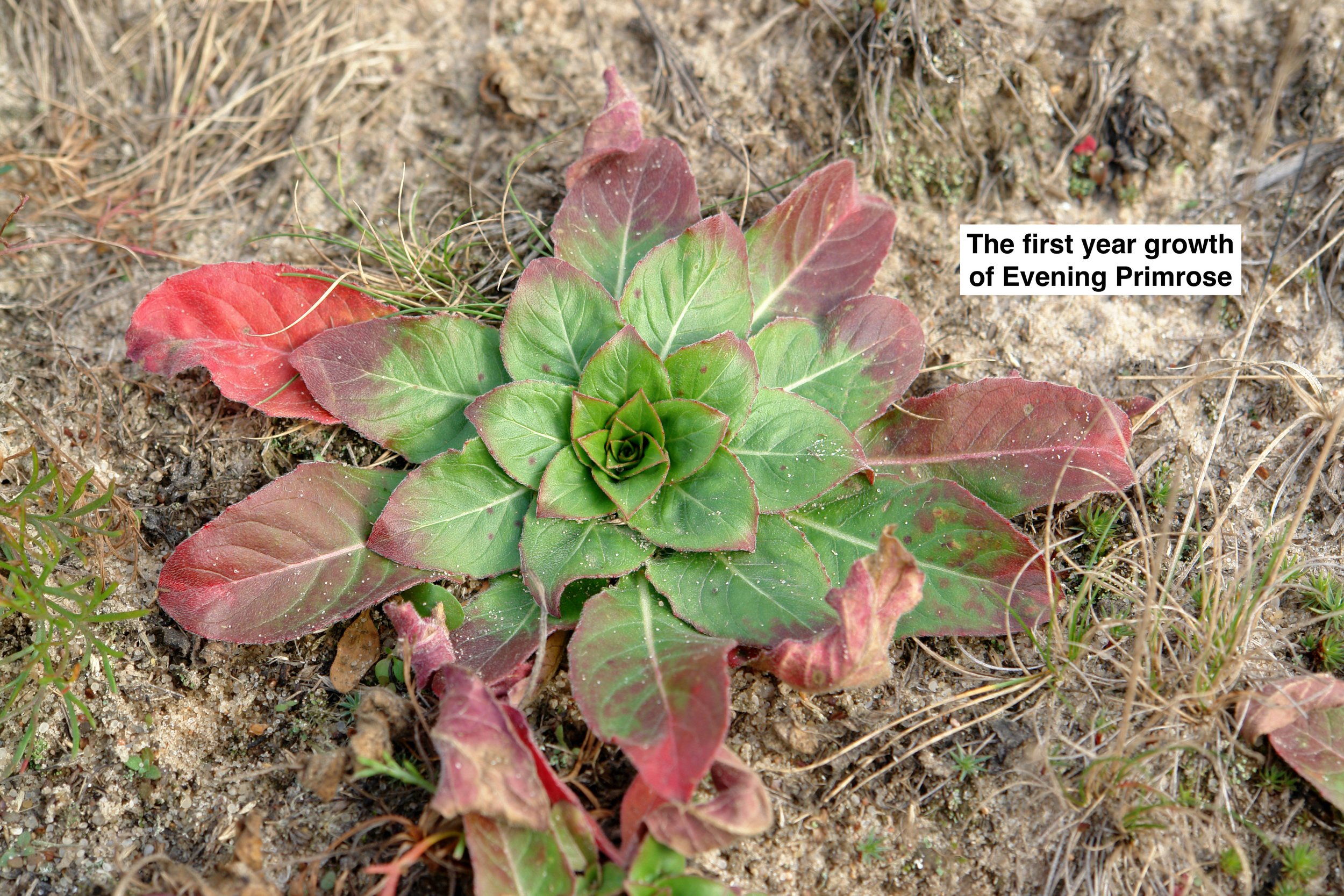

Slender Mountain Mint (Pycnanthemum tenuifolium) is a perennial native plant that branches in a way that creates a miniature bushy effect as its form. It grows easily in moist soils to average soils as long as it has full sun to partial sun, blooming most profusely in full-sun. It inhabits wetlands, moist to fairly dry soil prairies, meadows, gravelly areas along rivers, openings in woodlands, glades, and abandoned fields showing off a wide range of adaptability.

Click Images Below to Expand them.

Top left: Aged Pearl Crescents Top Right: A thread waisted wasp (Eremnophila aeronata) on the right with a sphecid wasp, Isodontia, on the left. Bottom Left: Great Gold Sand Digger Wasp (Sphex ichneumoneus) Bottom Right: Great Black Wasp (Sphex pensylvanicus)

The small white flowers attract many insects including long-tongued bees, short-tongued bees, wasps, flies, butterflies, skippers, and beetles. On this post the featured wasp species are completely non-aggressive as they're foraging for nectar and pollen. They would only get aggressive if a human disturbed their nests. Mammals avoid browsing the minty foliage which features a poisonous alkaloid.

Slender Mountain Mint has great staying power, able to persist among tallgrasses and short grasses for the long-run in prairies/grasslands. The small seeds stay fertile in the seed bank allowing it to pop up in old-field habitats where it hadn't existed for decades. Other mountain mint species have wide ranging adaptations like Slender Mountain Mint. If you have the opportunity to plant more than one species in your native meadow, then do so as they will likely bloom at different times and be slightly adapted to different conditions strengthening the integrity of your seed mix. In pollinator gardens Slender Mountain mint is a foreground plant in most plantings. The bright white helps highlight other midsummer flowering plants like Purple Coneflower. The fine textured foliage looks excellent before and after blooming. The seed heads carry some interest into the winter.

Companion Plants for Slender Mountain Mint

Click Images Below to Expand them.

Select/click the images above to expand them then click/tap to advance to the next picture. Also, Turn your cellphone side ways for horizontal pictures, and straight up and down for vertical pictures.

Companion Plants (Pictured Above): Golden Alexander, Sand Coreopsis, Penstemon digitalis, Penstemon calycosus, Ohio Spiderwort, Butterflyweed, Nodding Onion, Purple Coneflower, Great Blue Lobelia, Cardinal Flower, Rudbeckia fulgida, Prairie Dock, Early Goldenrod, Dwarf Goldenrod, Mistflower, Aromatic Aster

Germination Tips for Plugs: Cold Moist Stratify for 40 or more days then surface sow - compress into surface.

Receive 40% off of our Native Plant Propagation Guide/Nursery Model book when purchased as a package. deal with either our Native Meadowscaping book or our Native Plant Agriculture book at this link.

Learn about what our Native Meadowscaping book has to offer here at this link.

Learn about what our Native Plant Agriculture Vol. 1 book has to offer here at this link.

Learn about what our Native Plant Propagation Guide & Nursery Model has to offer here at this link.