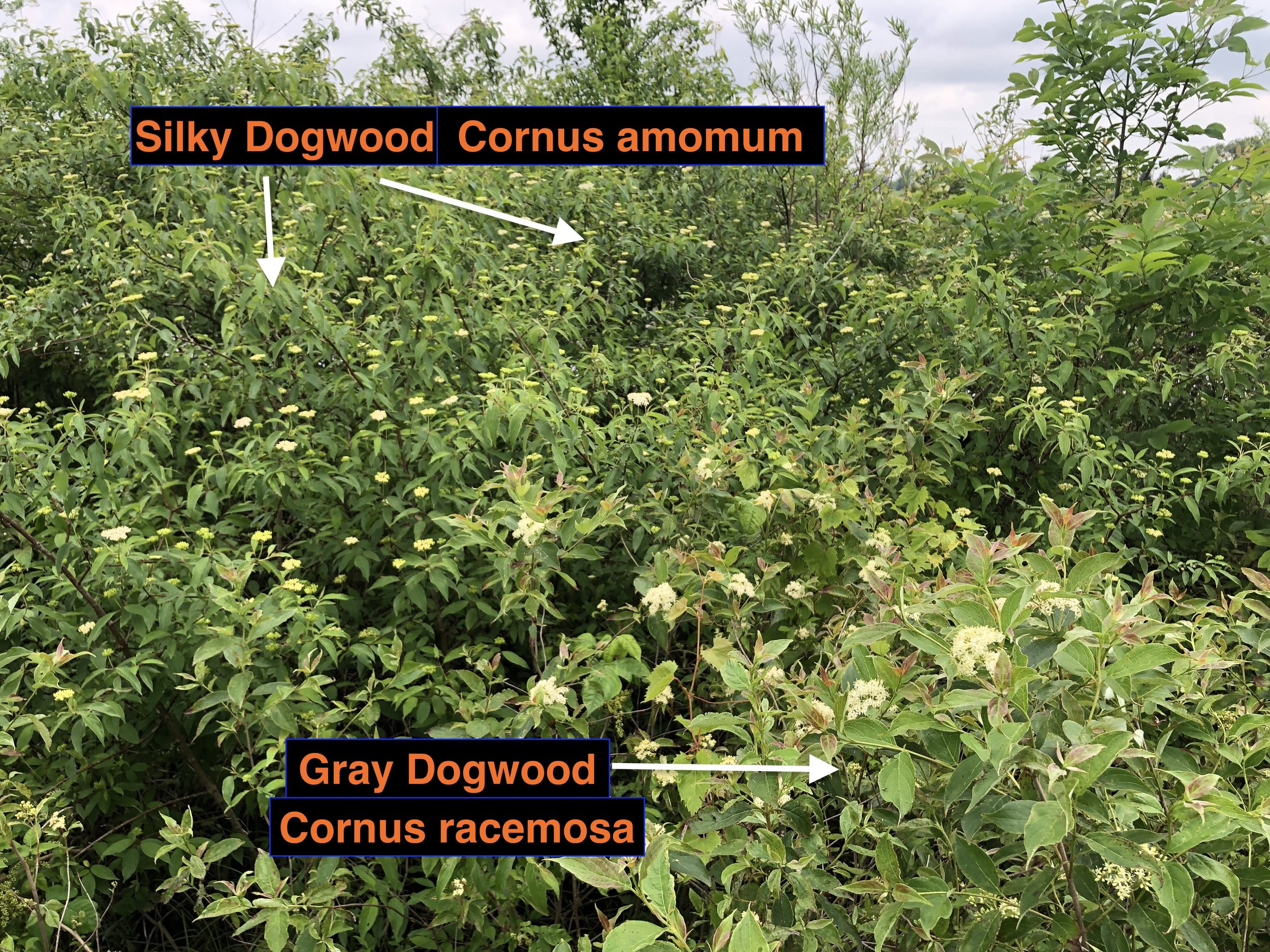

The early spring blooms of Wild Plum species (left), and mid to late summer fruiting of Dogwood species (right) plus their presence as insect host plants rebalances and increases the biological value of prairies.

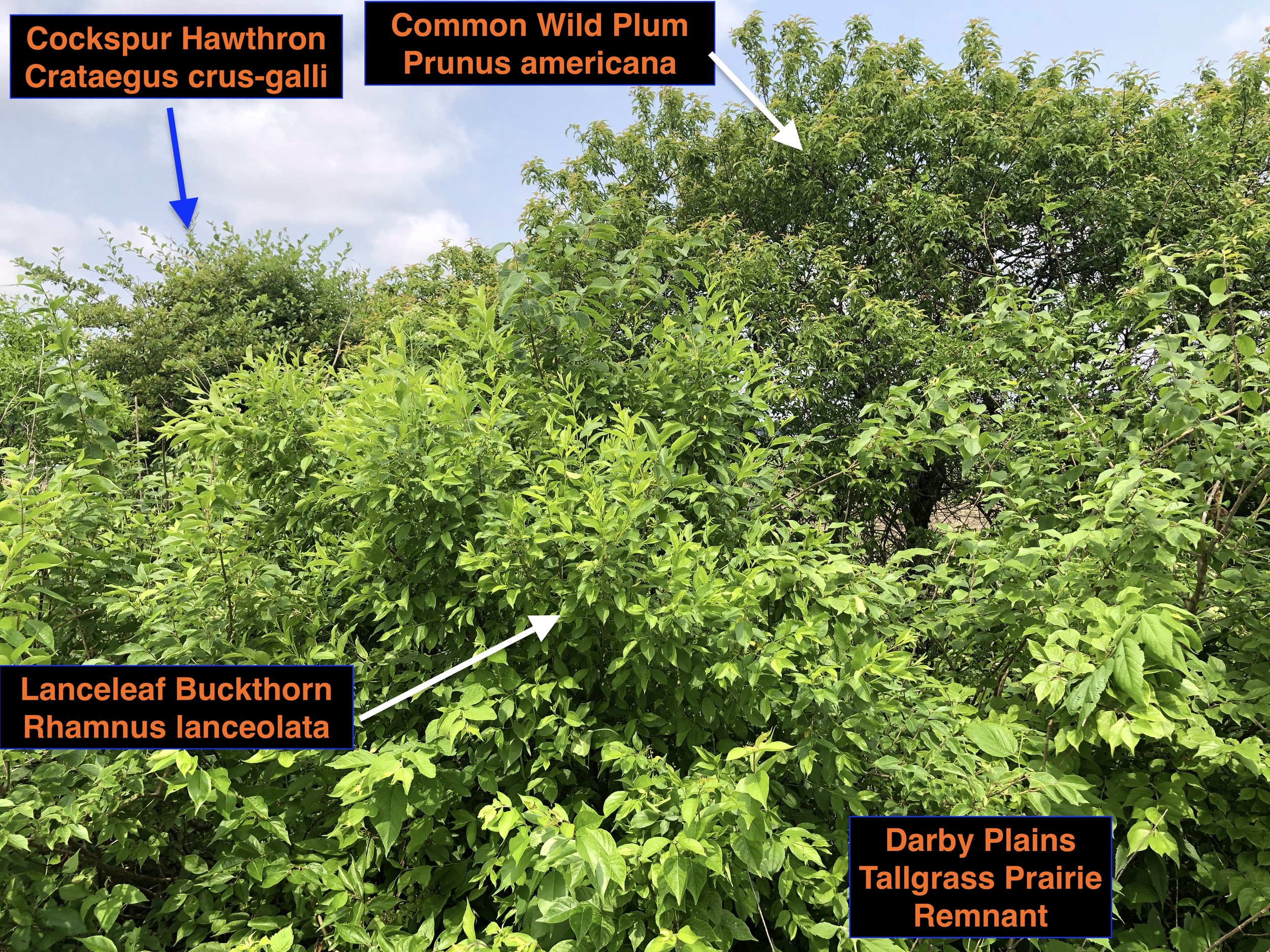

Throughout the eastern half of the U.S. and the midwest there's a pervasive misunderstanding of the natural place of native thicket species. If you read through pioneer journals and land surveyor accounts you'll notice many descriptions of the eastern grasslands featuring "a mile of thicket" or "shrubby fields/openings". Thickets so dense horses had to be routed around them. These descriptions come from a time where the interconnectedness of the ecosystems allowed for fires to spread wide and many of these accounts were made soon after the removal and displacement of Native American people/culture within which fire was set more often than would naturally occur. Despite that historical high frequency of fire, native thicket species were present and established part of the grasslands, savannas, and wetlands. This is because these shade intolerant thicket species evolved in the open environments of grasslands, savannas, and wetlands as permanent community members.

In a thicket’s maturity, the herbaceous layer is still present, but suppressed enough to not be able to carry a hot enough fire to burn the interior trunks. Only the edges can be burned back at this stage which is likely how they have co-evolved with fire prone landscapes. Still Groundnut and other herbaceous species are productive in this thicket understory.

Fire Adaptation of Native Thicket Species

While you may find remnants of the thicket aspect of the grassland ecosystem on man-made artificial edges (if not overcome by invasive plants), when you find an intact open-grown native thicket, you can start to see how they are actually fire adapted when the thicket is unfragmented and mature enough. The grassland and savanna - thicket community is made of up a mix of rhizomatous and singular formed trees/shrubs that, in combination, suppress the fuel of the herbaceous layer. This prevents a fire from being able to be hot enough to burn the interior of the thicket, however fire keeps the thicket from expanding endlessly as the edges of the thicket where the herbaceous layer produces enough fuel is always vulnerable to being burned back. See the interior of the pictured Wafer Ash, Roughleaf Dogwood, and Wild Plum thickets in the slideshow below to see this concept.

Most thicket species, without restoration efforts, now fail to form this continuous thicket micro-environment primarily due to invasive plant pressure and displacement from their grassland/savanna/wetland habitats to artificial man-made edges. This is the similar predicament grassland-savanna herbaceous plants are in; unable to expand or persist due to fragmentation from habitat loss (livestock feed production-corn/soy), and invasive plant pressure disrupting new establishment.

All of the fauna above are either specialists (the insects) or beneficiaries of 1 single thicket species, the American Hazelnut, demonstrating the biological value thickets provide to these communities. We exapanded on Hazelnut biology on this post here. But this is just one of many thicket species.

Why Thickets Matter - Food Chain Restoration

Thickets are dwarf-forests of the grasslands, savannas, and wetlands that produce what the herbaceous layer does not. For example, most native thicket species bloom in the spring and early summer; in Southwest Ohio that's April through mid June). This is also when the wetland, savanna, and grassland communities' herbaceous layers have little to no pollen/nectar. This matters because keystone pollinators like bumble bee species' queens rely on these spring blooming species to raise their first wave of female worker bees from eggs, who will then help expand the hive and pollinate many herbaceous wildflowers that bloom later in the year. Other solitary, early emerging native bee species can’t use the grassland/savanna/wetland ecosystems much at all without thicket species supplying their spring and early summer pollen/nectar supplies. Early emerging pollinators become limited to relying on the remaining spring ephemeral populations in forest ecosystems to sustain their populations. They also use forest trees such as Black Cherry, Black Gum, Sassafras, Red Maple and forest-thicket species such as Spicebush, Leatherwood, Black Haw Viburnum, and Maple leaf Viburnum. But all of these plant species are part of the forest ecosystem, distinct from the prairie-wetland-savanna ecosystems. The thickets are all the prairie-wetland-savanna ecosystems have to offer in spring/early summer.

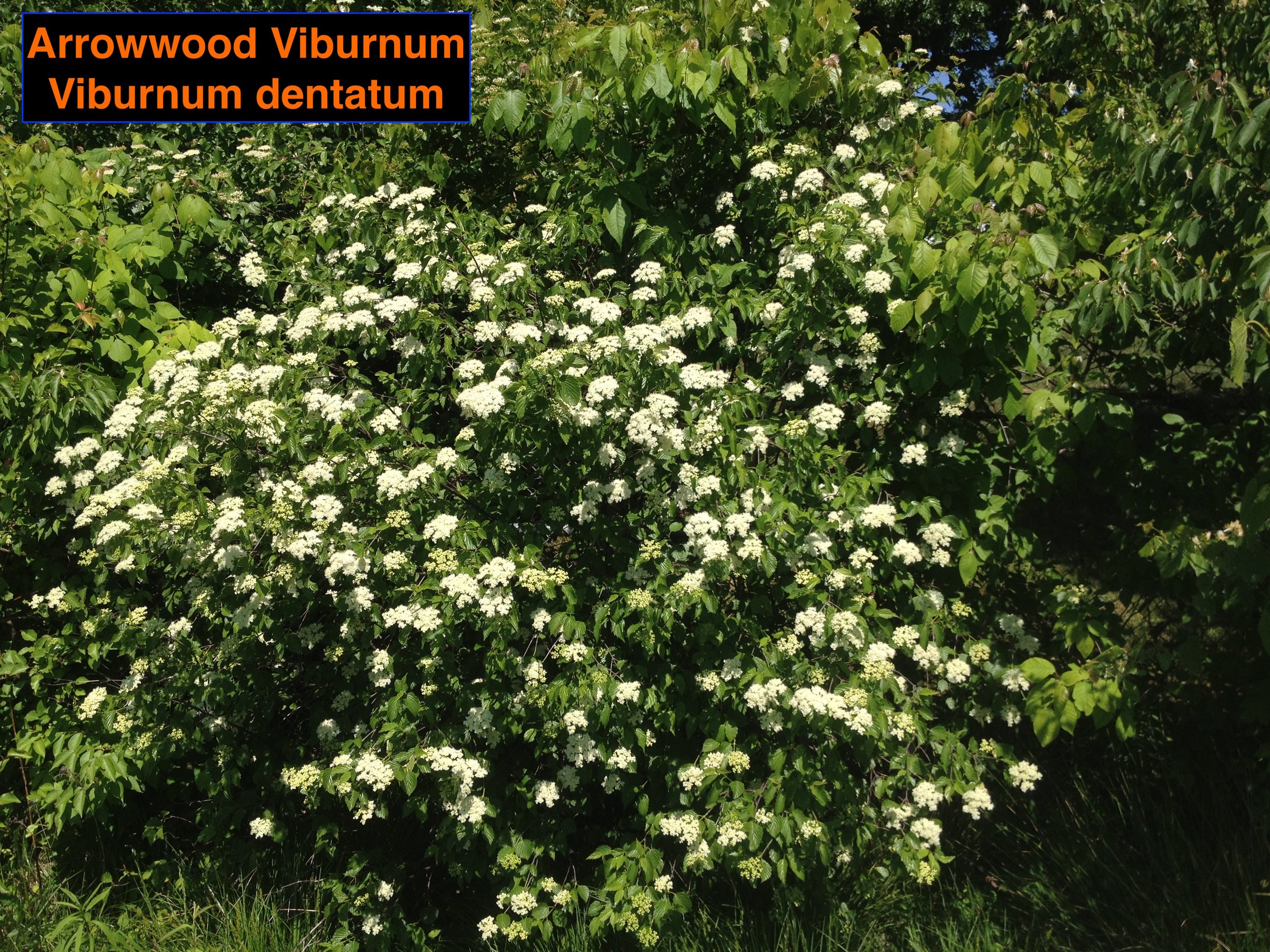

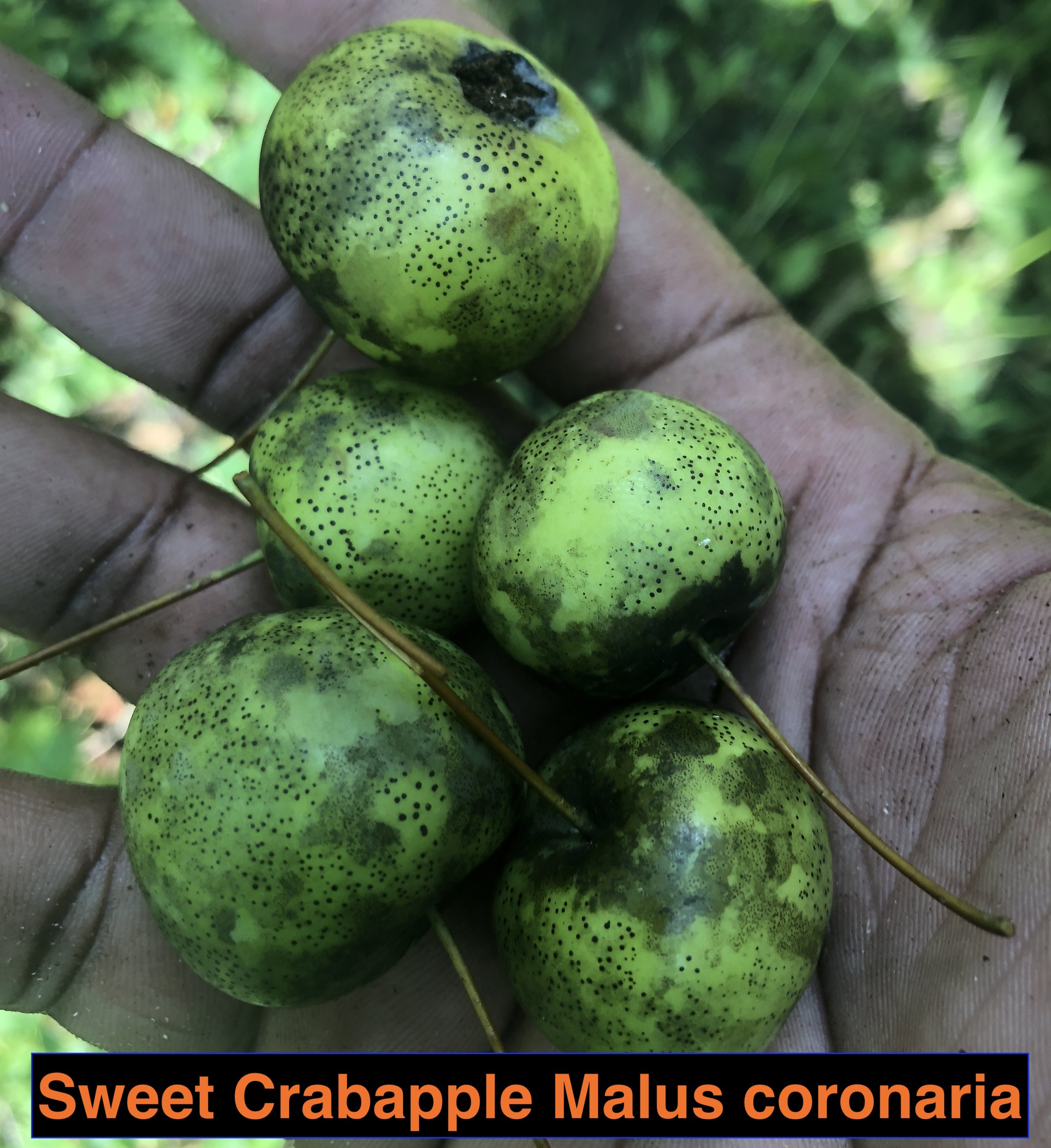

In addition to balancing the pollen/nectar production of the grasslands/wetlands/savannas, the contribution of the leaves alone of native thickets greatly enhances the diversity of insect production. Just add the combined potential caterpillar host numbers for Chokecherry, Wild Plum, Native Crabapples, Hawthorn, Native Roses, Viburnum species, and Hazelnut and you'll see there's a potential 1,300+ species of moths/butterflies that would be hosted, again, within these ecosystems if just those thicket species alone were given proper restoration attention.

Consider too; Modern Day Food Chains

In the absence of Bison, Elk, and Wolf; the major cyclers of the energy of the herbaceous layer of grasslands are nearly completely absent in the eastern half of the U.S. which makes the native thicket aspect of grasslands, wetlands, and savannas even more so relevant and valuable in modern food chains. Outside of insect production, the largest remaining cycler of energy are native rodents that are preyed upon by lager mammals, though thickets support rodents too primarily because rodents eat the seeds of most of the thicket species. Each thicket species produces a fruit or seed that is edible to either mammals (including rodents), birds, and insects as well as the insect diversity contribution of the leaves/vegetation as host plants for thousands of thicket genus or species specialized insects.

Where to Restore Native Thickets

Small fragmented remnant prairies are more-so botanically significant than biologically valuable (due to small size and fragmentation), and that botanic herbaceous diversity should be protected from thicket growth, of course. But when it comes to the thousands of acres of prairies being restored/reconstructed, and larger remnant prairies; the restoration of savanna, wetland, and grassland ecosystems should include the thicket aspect of the community for appropriate biological/food chain value.

Understand the value and place of native thickets on their unique and essential contributions via distinct insect production, micro-climate creation/shelter, and fruit/seed/nut production that the herbaceous layer cannot produce. The modern maintenance of the thicket-less grassland/savanna is a misinterpretation of the biology of these open communities. These specific thicket species can only persist in grassland, wetlands, and savannas due to their shade intolerance which partly demonstrates their co-evolution and interdependence as these are the only ecosystems that hold a viable niche.

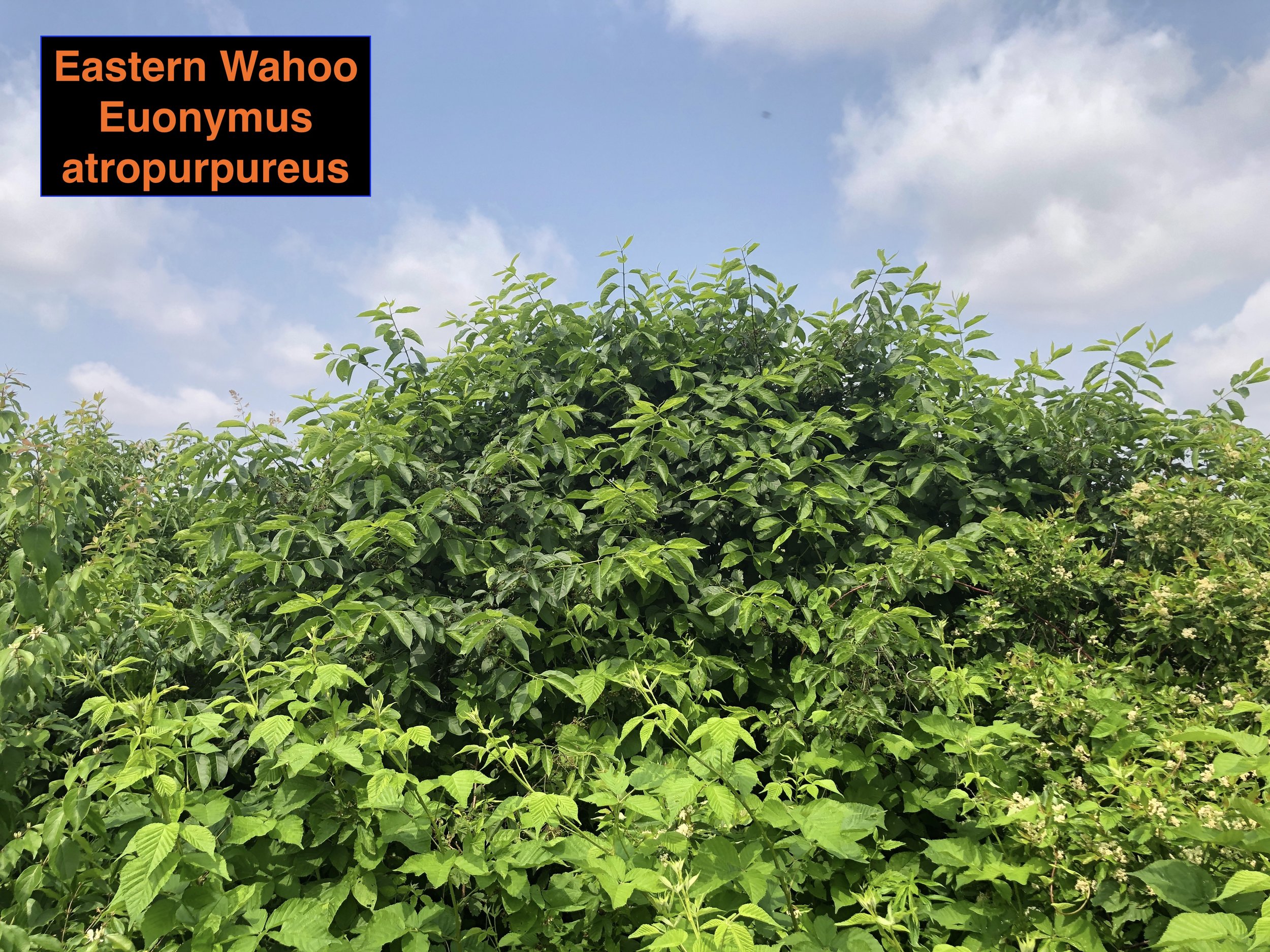

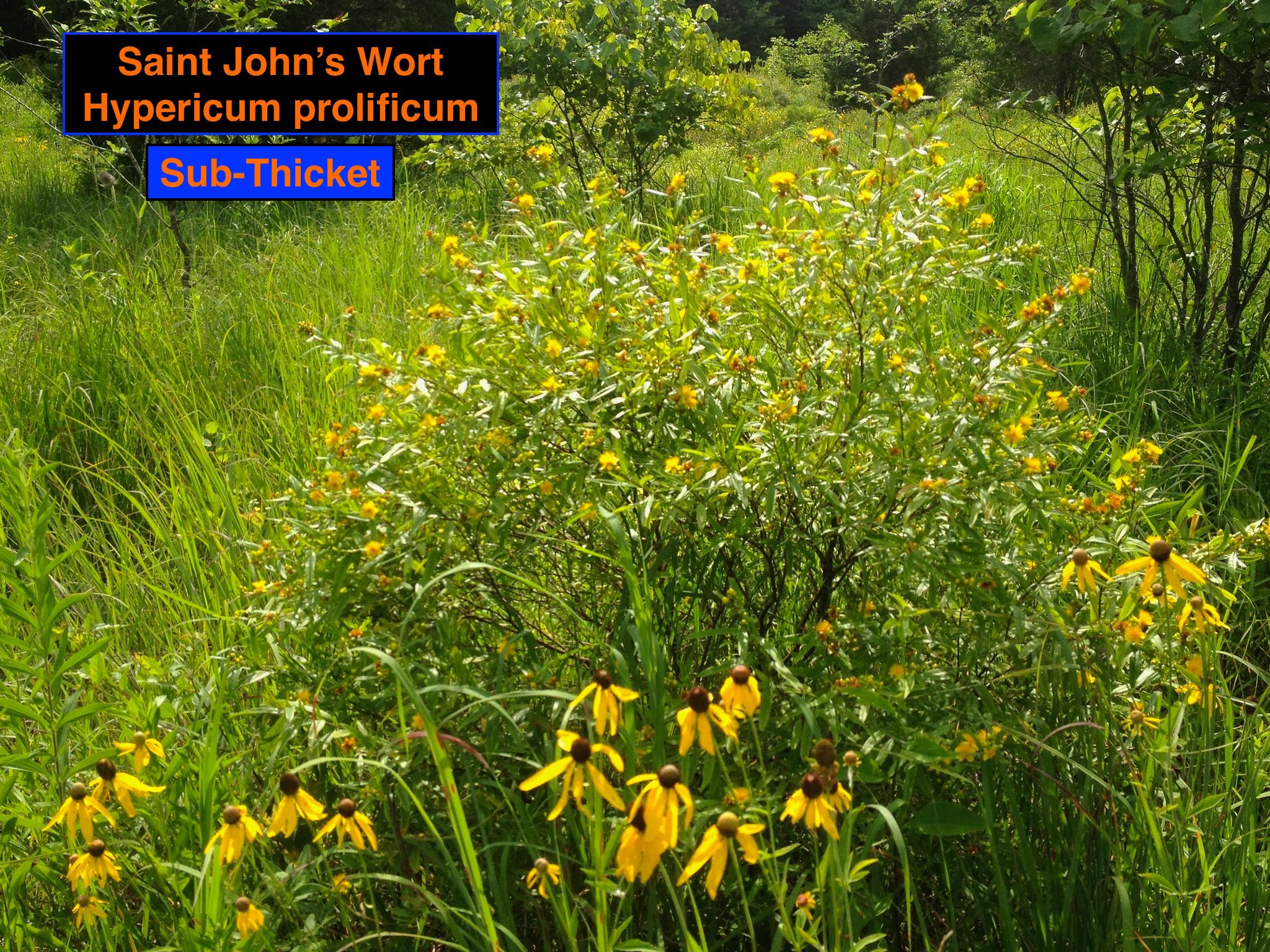

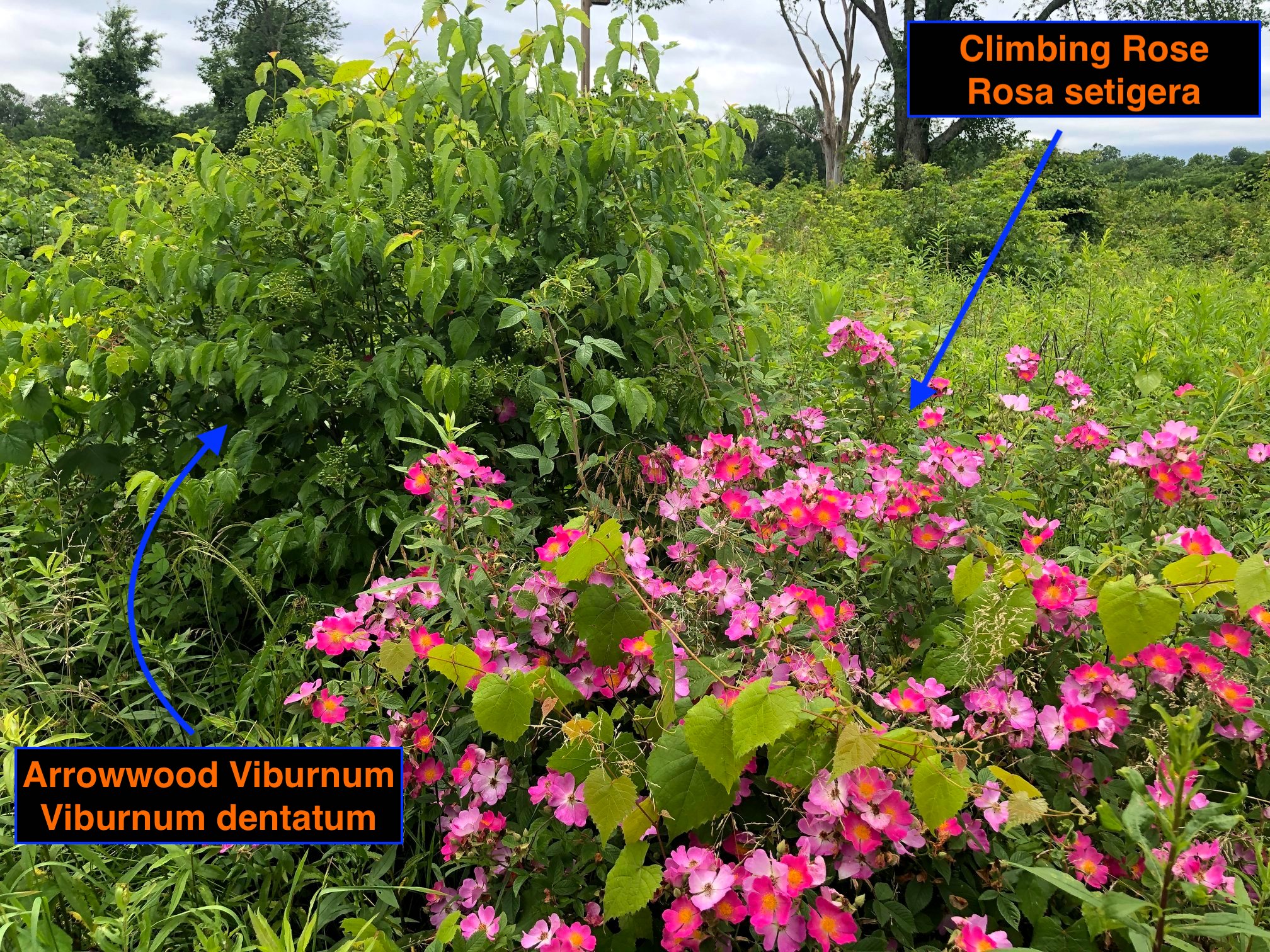

Thicket Species Slideshow

Pictured in this Slideshow is a sample of native thicket species. This slideshow only represents a portion of thicket species native to the Eastern Half of the U.S. There are many Thicket, and Sub-Thicket species native to the open environments of the U.S. What we’re referring to as thicket species can co-exist with each other such as Wafer Ash, Wild Plum species, Devil’s Walking Stick, Hawthorn species, Hazelnuts, Dogwood species, and Lance-leaf Buckthorn. Sub-Thicket species can’t co-exist with those taller thicket species, and have evolved other ways of being a part of the herbaceous layer such as Blackberry species, native Rose species, Coralberry, Native Spirea, Blueberries, Lead Plant, Saint John’s Wort, and New Jersey Tea.

Notice how +85% of these Thicket species bloom in the spring or early summer before the herbaceous layer of the savanna, wetland, and grassland ecosystems is producing much nectar/pollen at all.

Thicket Species in this Slideshow: Wafer Ash, American Hazelnut, Common Wild Plum, Quapaw Wild Plum, Chickasaw Wild Plum, Smooth Sumac, Winged Sumac, Staghorn Sumac, Fragrant Sumac, Rusty BlackHaw Viburnum, Arrowwood Viburnum, Lanceleaf Buckthorn, American Hazelnut, Silky Dogwood, Roughleaf Dogwood, Gray Dogwood, Nine Bark, Prickly Ash, Eastern Wahoo, Sweet Crabapple (Native), Carolina Buckthorn and Scarlet Hawthorn.

Sub Thicket Species in this Slideshow: Smooth Rose, Climbing Rose, Swamp Rose, Coralberry, Blackberry, Meadowsweet Spirea.