A short Educational ecology article written by Solomon Doe - Author/Owner of Indigenous Landscapes

View this article on a tablet, laptop, or screen larger than a phone screen to get the maximum quality view of the pictures.

The traits and values of Bur Oak - Quercus macrocarpa

The Bur Oak has one of the larger native ranges and is of the most adaptable native Oak trees (Quercus sp.) in the United States. They can turn open grasslands into tree dotted savannas. In regions with natural grasslands, they can also grow closer to form a woodland with a lush herbaceous understory. They’re able to grow out of drier rocky slopes, as well as compete in deep silty moist bottomland or alluvial soils. Periodic flooding, annual wildfires, seasonally-high water tables, alkaline soils; sand, silt, gravel, and clay...none of these conditions can by themselves; exclude the Bur Oak from growing successfully. While Bur Oaks planted in acidic soils most often thrive, naturally they are more frequently found in higher PH soils of over 6.5+ PH. The Bur Oak's thick bark develops at a young age allowing it to become quite fire resistant within less than a decade of growth. So if a grassland or savanna naturally went without a fire even for 6 to 10 years and new Bur Oak sapling could develop thick enough bark during that time to become a 150+ year old fixture within that landscape. These Savanna Bur Oaks form helps to support a wide diversity of plants and animals in comparison to pure grassland or pure forest, acting as an overlap of both ecosystems. For context, a grassland is a native grass, wildflower, and thicket dominated landscape with very few trees. A savanna is a grassland with some trees often growing in clusters as islands of trees within the grassland. A woodland is often described as 70% to 90% tree canopy coverage with a herbaceous understory commonly dominated by wildflowers. Forests are typically described as 90 to near 100% tree canopy coverage.

Prominent Moth Caterpillars (Dantana species) body consuming Bur Oak leaves as a group. When you approach them, they perform a synchronized twitch to scare off or confuse predators.

The Immense Ecological Value of Oaks

Collectively Oaks are known to host over 500 different species of native moth/butterfly caterpillars. Our existing Oak species have been found in fossils dating back about 23 million years ago which is around the same time Grasslands evolved as an ecosystem. When people discuss the insect value of native plants the topics are usually centered around how many Lepidoptera (moth and butterfly) larvae the species within a genus can host or the variety of pollinators their flowers support. In actuality the ecological value of a native plant cannot be fully realized by only measuring these two categories. With trees, their wood and decaying leaves support native Beetle larvae and adult Beetles. Their leaves support various insects with the order of Orthoptera that features katydids, crickets, grasshoppers, and locusts. Ants tend to aphids and other sap sucking insects siphoning liquid from the vegetation. Underground various insects, bacteria, and fungi are interacting with the root systems. Wasps and Birds glean the vegetation for insects acting as natural controls to keep the trees from being over-consumed. Rodents seek out various tree seeds as primary foods sources and that energy is worked up into the food by various rodent predators. You could look toward most terrestrial orders of insects and connect the food chain from native plants up into insects and other small organisms; up further into larger animals.

A typical acorn kernel size of a Bur Oak

The Native Plant Agricultural Value of the Bur Oak

The Bur Oak, like all Oaks, would benefit from a concerted effort to agriculturally evaluate and select for heavy biennially bearing trees or the rare annual bearing trees. Naturally Oaks and other nut bearing trees delay and concentrate heavy crop years to control the population of rodents that can destroy the majority of a year’s crop. Have “up years” and “down years” prevents rodent populations from being sustained at their maximum potential. But Oaks do have the biological capability to bear nuts annually or biennially if these qualities are selected for through breeding or selecting wild occuring bearers. This fact is demonstrated by the Swamp White Oak Cultivar “Buck’s Unlimited” which is an annual bearing Swamp White Oak selection. This cultivar selection of a wild occurring Swamp White Oak was found to annually bear good crops of acorns and its named “Buck’s Unlimited” is marketed to hunters wanting to plant acorn crops for deer. Compared to Most Hickories and Walnuts, Oaks invest very little defensive energy in their acorns outside of tannins which are an anti-nutrient that makes the nuts bitter. Acorn shells/husks are very thin, and with exception to the Bur Oak’s caps, acorn caps are most often small as well. The smaller investment of energy into defense, this likely gives Oaks an efficiency and bearing ability edge over most Hickories and Walnuts. Once more consistent bearing Oak species are selected, they will likely top all hickories, most pecans, and walnuts as far as calories produced per acre due to this high proportion of nutmeat vs. shell. This makes their potential value to Native Plant Agriculture very high when you also factor in their ecological value.

To learn how to make acorn flour out of acorns there’s many YouTube videos out there. Cold water leaching is the best method and retains the most nutrients in the resulting nut flour vs. hot water leaching. The flour is used similar to wheat flour, but creates a heavier and denser “bread” than what flour. Wheat flour is often used in recipes that include acorn flour to give it a lighter fluffier texture. Indigenous people’s across the world where Oaks are native used acorns as a staple crop of their diet by leaching the bitter tannins out of the nuts.

A Bur Oak reaches over the street towards a stand of PawPaws in the fall. The Bur Oak twigs and leaves on the ground are from squirrels cutting the acorns down to the ground,

Neighborhood Applications of Bur Oak

In Neighborhoods, Bur Oak offers one of the widest spreading, shade giving - majestic canopies on the block. The thick bark houses numerous insects which can be evidenced by the amount of bark foraging birds that use Bur Oak. While the acorns are a mess to clean up for those who don’t value them, in yards of those who value them; Bur Oak acorns are both toys to the children and sustenance for the wildlife. Crafty households may turn the large acorns into flour for bread-like products. The fall color isn’t significant but the abstractly cut leaves give a rich dark green color throughout the summer. Oaks are one of the best trees to cool the temperature down of a neighborhood through allowing an Oak to get as large as it can away from buildings and power lines. Neighborhoods with underground utilities free of power lines are prime placement for Bur Oak and other Oak trees. Oaks create cool spots that greatly improve outdoor livability for humans in areas with hot summer environments. While they can cool down large areas, they’re aren’t ideal for placing too close to houses as they can develop to a size that can crush a house if they happen to fall. 40 feet of distance from houses and other valued buildings is typically sufficient for Bur Oak placement. Applicable to all hillside aspects; N,E,W, and S if the soil is at least 35 inches deep before hitting solid bedrock - or flatter ground. Height is 55’ to 80’. Wind Pollinated though some native bees collect pollen from Oak catkins in the spring. Shade Tolerance: 2/5

Typical Bur Oak leaves in the fall.

Common Canopy Native Tree Associates of Bur Oak

The following species are commonly found growing near by Bur Oak and if you’ve identified a soil type that fits Bur Oak for your restoration; these trees will also fit in your reforestation project.

When landscapes aren’t historically maintained by fire creating fire tolerant savannas and woodlands; Bur Oak associates with species and in soils of 6.7 PH and higher into the alkaline range.

Forest Canopy Associates

Weakly Acidic to Alkaline Soil preferring Associates Ohio Buckeye - Aesculus glabra, Shumard Oak - Quercus shumardii,, Chinquapin Oak - Quercus muehlenbergii, Blue Ash - Fraxinus quadrangulata, Kentucky Coffee Tree - Gymnocladus dioicus, Shellbark Hickory - Carya laciniosa.

PH Generalists Associates: Bitternut Hickory - Carya cordiformis, Pecan - Carya illinoinensis, Black Maple - Acer nigrum, Sugar Maple - Acer saccharum, American Linden - Tilia americana, American Elm - Ulmus americana, Slippery Elm - Ulmus rubra, Hackberry - Celtis occidentalis, Black Walnut - Juglans nigra

Fire Maintained Savanna and Woodland Canopy Associates

Shellbark Hickory - Carya laciniosa, Bitternut Hickory - Carla cordiformis, Red Hickory - Carya ovalis, Shagbark Hickory Carya ovata, Red Oak - Quercus rubra, White Oak - Quercus alba, Shumard Oak - Quercus shumardii,, Chinquapin Oak - Quercus muehlenbergii, Blue Ash - Fraxinus quadrangulata

A Bur Oak leaf with a slightly larger leaf margin than the one above. This is in the fall.

Propagation Tips: Collect Bur Oak acorns in the fall and outdoor cold moist stratify for the winter. There’s no need to remove the caps until the spring when they will easily fall off or you can remove them in the fall. Make sure your container has drainage for the rain, and rodent protection using hardware cloth to cove the top. Bury the container 3/4ths underground to protect from the coldest winter temperatures. Bur Oak acorns will start to root in mid to late winter even though they are technically a “White Oak” which typically root in the fall. So sow them early, by mid to late winter. Chicken wire exclosures will keep out squirrels, mice and chipmunk control or relocation may be required.

The high surface area of the thick furrowed bark may promote more insect use compared to less textured bark Oaks. This bark is quite fire proof when it comes to surviving grassland fires.

These Bur Oaks are going into fall color, which typically isn’t a fantastic display for Bur Oak.

The husk of a Bur Oak acorn has fringe-like fibers around the edges of the cap. Most Oak species do not have this feature.

Give Bur Oak a large width to spread out overtime in neighborhoods. If they’re out in the open, they’ll become wider than they are tall.

Most Bur Oak dominated woodlands and savannas transition into forests once man-made fire stops maintaining them.

Bur Oak dominated woodlands and savannas were a common ecosystem where Grasslands and Native Trees intermingled. This landscape was widely promoted by Indigenous People’s fire pre European contact.

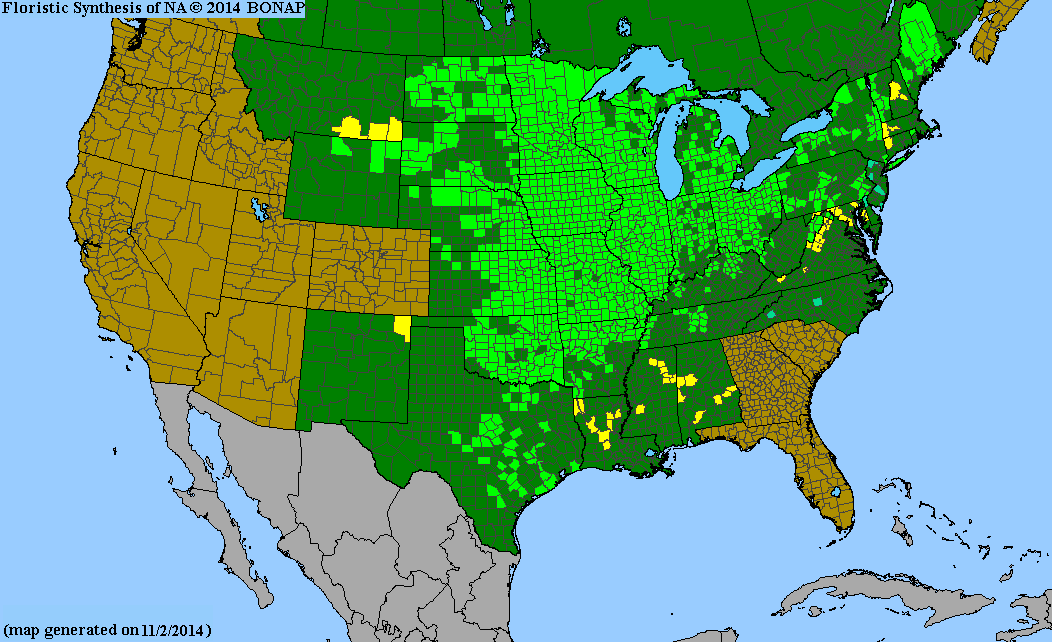

Bur Oak Native Range Map

Key for the Map Above

Light Green = Reported to an herbarium for the county as native and wild occuring.

Teal = Reported to an herbarium for the county as present and introduced by man.

Yellow = Reported to an herbarium for the county as present but rare.

Green = Reported to an herbarium as present in the state.

Orange = Once reported to an herbarium as native but now considered extinct in that county.

When considering planting a native plant, always google search the scientific name aka latin name with the word “bonap” to look up its native range as reported by country records submitted to herbariums. If the plant is native within 100 miles of your location it will be more ecologically applicable than plants native further away. The further away a plant is native, often, the less ecologically applicable it becomes.